By Arun Arokianathan

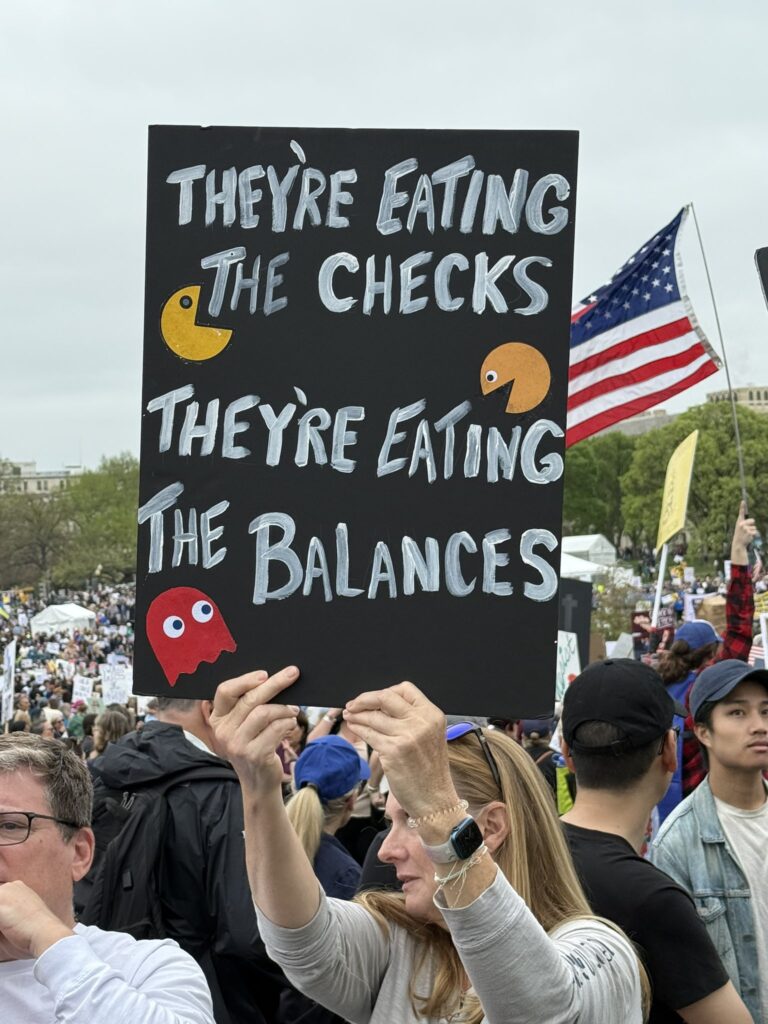

Voices are rising in streets across the United States. From coast to coast, crowds are gathering, holding signs and chanting, “Enough is enough!” These protests, sparked by frustration with President Donald Trump’s administration, are more than just political noise—they reflect deep worries about the economy and everyday life.

Voices are rising in streets across the United States. From coast to coast, crowds are gathering, holding signs and chanting, “Enough is enough!” These protests, sparked by frustration with President Donald Trump’s administration, are more than just political noise—they reflect deep worries about the economy and everyday life.

The April 5 protests, held under the banner of “Hands Off!”, marked one of the largest single-day demonstrations in recent U.S. history. According to reports from several media organizations, Over 1,000 protests took place across all 50 states and more than one million people participated simultaneously, showing just how widespread and coordinated the public outcry has become. From small towns to major cities, people united across backgrounds to oppose a broad range of policies.

I couldn’t help but think how quickly the tables are turning. Donald Trump hasn’t even completed three months in office, yet he’s already facing a level of opposition that most presidents only see years into their term. This is supposed to be his honeymoon period — a time traditionally marked by high approval ratings, goodwill from the press, and political breathing room to implement bold policies. But that grace period, once lasting over two years in the early 20th century, has shrunk dramatically. Today, it barely stretches six months — and for Trump, it seems to have ended before it even began.

The scenes bring to mind Sri Lanka’s 2022 “Aragalaya” uprising, when economic mismanagement pushed ordinary citizens to overthrow their government.

While protests against the administration’s policies are growing, it may be premature to suggest President Trump could face a similar fate as Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. No U.S. president has ever been directly removed from office by public protests in American history. Yet history is not static – it evolves based on emerging situations.

As political historian Doris Kearns Goodwin noted, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” In politics, conventional wisdom can be overturned by exceptional circumstances. The unlikely becomes possible when economic conditions deteriorate beyond a certain threshold.

The Sri Lankan Warning: When Citizens Reach Their Limit

The case of Sri Lanka offers important insights into how economic crises can lead to political upheaval.

In early 2022, Sri Lanka faced its worst economic crisis since independence. Years of mismanagement had left the country bankrupt. Basic necessities became luxuries overnight.

Small protests began in March 2022. By April, they had exploded into a nationwide movement. The “Aragalaya” protests became famous worldwide. Citizens set up permanent camps near government buildings. They named their main encampment “GotaGoGama” (“Gota Go Village”). It was a direct demand for President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to resign.

Sri Lankans started as ordinary people, not revolutionaries. They were teachers, doctors, office workers, and farmers. At first, they tried to adapt to worsening conditions. They skipped meals. They rationed medicine. They shared transportation costs.

Then conditions got worse. Food prices doubled, then tripled. Fuel became nearly impossible to find. Power outages stretched to 13 hours daily. Hospitals ran out of essential medicines. Schools closed because students and teachers couldn’t afford transportation. Government workers went unpaid for months.

President Rajapaksa seemed untouchable. His family controlled the government. Six of his relatives sat in parliament. Four held key ministerial roles. He had full backing from the military. He was a former defense secretary who had won the civil war. The country’s powerful Buddhist monks supported him.

None of that mattered when people couldn’t feed their families. The middle class saw their savings vanish in weeks. By July 2022, Rajapaksa fled the country. He was chased from power by peaceful protesters who had simply reached their breaking point.

Different Systems, Different Outcomes

The American political system differs significantly from Sri Lanka’s. The U.S. has stronger institutional checks and balances, a federal system that distributes power, and a more robust economy overall.

These differences make direct comparisons difficult. What happened in Sri Lanka may not be replicable in the American context. The path from economic discontent to regime change involves many variables unique to each country’s political culture and institutions.

However, economic hardship creates universal human responses. When basic needs go unmet for extended periods, people become desperate regardless of nationality. The threshold may be different, but every population has a breaking point.

Learning from History

While no American president has been directly ousted by protests, history shows that sustained economic difficulties can dramatically reshape political landscapes.

The Great Depression fundamentally altered American politics for generations. The 2008 financial crisis spawned both the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street movements, changing both major parties’ trajectories.

Economic crises create political vulnerabilities. They erode public trust in institutions. They make previously unthinkable political outcomes possible.

As political scientist Francis Fukuyama observed, “Legitimacy is the currency of power. When it’s depleted, even the strongest governments become fragile.”

The Kitchen Table and the Ballot Box

In established democracies like the United States, economic discontent typically finds expression through electoral channels rather than through direct action.

The constitutional system provides regular opportunities to remove leaders through voting. This institutional safety valve has historically prevented the kind of extra-constitutional changes seen in countries with less developed democratic traditions.

Yet mass movements can significantly influence electoral outcomes. They shape media narratives. They energize voter turnout. They force issues onto the political agenda.

Whether current economic challenges will translate into electoral consequences remains to be seen. Much depends on whether policy adjustments address the underlying concerns driving public discontent.

Conclusion: Watching the Warning Signs

The lessons from Sri Lanka are instructive if not perfectly applicable. Even the most powerful governments become vulnerable when people can’t meet basic needs. Economic mismanagement created an unexpected political outcome in a system that seemed impervious to change.

While it would be an overstatement to predict a similar fate for the current U.S. administration, the historical pattern is clear: prolonged economic pain creates political instability. The exact form that instability takes varies by culture, system, and circumstance.

As one Sri Lankan protest leader reflected after their movement succeeded, “We never set out to change history. We just couldn’t feed our children anymore. Everything else followed from that simple fact.”

For now, America’s political future remains uncertain. The democratic system has weathered economic storms before. But as economic historians remind us, past performance does not guarantee future results.

Arun Arokianathan is an Asia Journalism Fellow and a Chevening South Asia Journalism Programme (SAJP) Fellow. Follow his work and insights on Twitter @aroarun and connect with him on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/in/arunarokianathan/