By Arun Arokianathan

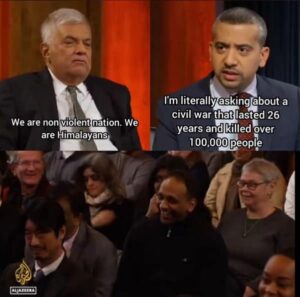

In a widely publicized interview with Mehdi Hasan for Al Jazeera, former Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremesinghe claimed that Sri Lanka is a non-violent nation. Hasan swiftly countered, pointing to the 26-year civil war that claimed over 100,000 lives. While it is true that the majority religion in Sri Lanka promotes non-violence and tolerance as core values, the country’s actual history tells a different story.

If I were to challenge this claim with personal emotions, politicians would likely dismiss my argument by pointing out my Tamil heritage and accusing me of bias. Instead, I chose to approach this topic with rigorous, fact-based research. Using the most advanced AI research tool available today, Perplexity, I conducted an in-depth analysis of Sri Lanka’s history of violence.

Here is what I uncovered.

A History of Violence: Sri Lanka’s Turbulent Journey from Colonial Rule to Present Day

Sri Lanka, an island nation off the southern coast of India, has experienced numerous violent episodes throughout its modern history, with deep-rooted ethnic, religious, and political dimensions. From the brutality of the 26-year civil war to insurgencies, pogroms, and terrorist attacks, violence has shaped the nation’s trajectory in profound ways. The Sri Lankan Civil War (1983-2009) stands as the longest and most devastating conflict, resulting in over 150,000 deaths and displacing hundreds of thousands more. However, this represents just one chapter in a complex history of violence that includes multiple anti-Tamil pogroms, leftist insurrections, and more recent terrorist attacks. This report examines the historical context, key events, and lasting impacts of major violent episodes in Sri Lanka’s history, revealing patterns of ethnic tension, political opportunism, and the challenging path toward reconciliation.

The historical roots of Sri Lanka’s ethnic tensions can be traced back to ancient settlements and subsequently amplified by colonial policies. Sri Lanka’s population primarily consists of the Sinhalese ethnicity, an Indo-European group that arrived on the island around 500 BCE from northern India. The Tamils, who originated from southern India, maintained contact with the Sinhalese and underwent significant migration between the 7th and 11th centuries CE1. Beyond ethnic differences, these groups also maintained distinct religious identities, with the Sinhalese predominantly practicing Buddhism and the Tamils mainly following Hinduism1.

When the British colonial administration took control of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1815, the demographic composition featured approximately 3 million Sinhalese and around 300,000 Tamils1. British colonial rule, which lasted from 1815 to 1948, dramatically altered the island’s ethnic balance and power dynamics in ways that would later fuel conflict. The British administration transported nearly one million Tamils from India to work in the coffee, tea, and rubber plantations, significantly changing the demographic landscape1. More problematically, the British colonial system deliberately favored Tamils in government positions and established superior educational facilities in Tamil-majority northern regions1. This preferential treatment naturally fostered resentment among the Sinhalese majority, establishing dangerous fault lines that would later erupt into violence.

The colonial policy of divide-and-rule created an environment where ethnic identity became increasingly politicized. The British governance model encouraged competition between ethnic groups rather than cooperation, setting the stage for post-independence tensions. By the time of independence in 1948, these colonial-era disparities had created a society where ethnic identity had become inextricably linked to political and economic opportunity, a volatile combination that would later explode into decades of violence.

Following independence from Britain in 1948, Sri Lanka’s new government implemented a series of policies that systematically discriminated against the Tamil population. In a move that particularly alienated Tamils, the government declared Sinhala the sole official language, effectively excluding Tamils from government employment opportunities1. Additionally, legislation was enacted that made it nearly impossible for Indian Tamils to obtain citizenship, further marginalizing a significant portion of the population1. These discriminatory policies served as the initial triggers for what would eventually become the Sri Lankan Civil War.

The post-independence era saw several violent episodes targeting the Tamil community before the full-scale civil war erupted. These include the Gal Oya riots of 1956, the anti-Tamil pogrom of 1958, and additional pogroms in 1977 and 19814. These incidents demonstrated an escalating pattern of communal violence against Tamils, often with political backing. Each episode eroded inter-ethnic trust and pushed Tamil political movements toward more radical positions, including growing support for separatism.

The Tamil response to discrimination initially took the form of non-violent protests and political advocacy. However, as peaceful means failed to achieve meaningful changes and state-sponsored discrimination continued, more militant elements gained prominence within the Tamil community. Young Tamils, particularly those facing limited economic opportunities and continuous discrimination, became increasingly radicalized. This environment provided fertile ground for the emergence of militant groups, most notably the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which would eventually lead the armed struggle for a separate Tamil state.

The event widely recognized as the catalyst for the full-scale Sri Lankan Civil War occurred in July 1983, in what became known as “Black July” (Tamil: கறுப்பு யூலை; Sinhala: කළු ජූලිය). This anti-Tamil pogrom represented a turning point in Sri Lanka’s history, transforming simmering ethnic tensions into an outright armed conflict that would last for decades. The immediate trigger for the violence was a deadly ambush on a Sri Lankan Army patrol by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) on July 23, 1983, which killed 13 soldiers4. However, evidence suggests the subsequent pogrom was not merely a spontaneous reaction but rather a premeditated campaign of violence.

On the night of July 24, 1983, anti-Tamil rioting erupted in Colombo, the capital city, before rapidly spreading to other parts of the country4. Over seven days, predominantly Sinhalese mobs attacked, burned, looted, and killed Tamil civilians in a devastating display of communal violence. The violence later expanded to target all Indians, with even the Indian High Commission coming under attack and the Indian Overseas Bank being completely destroyed4. The death toll estimates from this week of terror vary widely, ranging from 400 to 3,000 according to different sources, while the Tamil Centre for Human Rights places the figure much higher at 5,638 killed4. Beyond the human cost, approximately 150,000 people became homeless, 18,000 homes and 5,000 shops were destroyed, and the economic damage was estimated at $300 million4.

Black July is particularly significant not only for its brutality but also for its political dimensions. The pogrom was initially orchestrated by members of the ruling United National Party (UNP), suggesting state complicity in the violence before it escalated into widespread public participation4. The government’s failure to protect Tamil citizens—and indeed evidence of active involvement in the violence—destroyed any remaining trust between the Tamil community and the Sri Lankan state. For many Tamils, Black July confirmed their worst fears: that they could not safely coexist within the Sri Lankan state and that a separate homeland might be their only option for survival.

The events of Black July had profound and lasting consequences for Sri Lanka. The pogrom catalyzed Tamil militancy, with thousands of young Tamils joining separatist groups, particularly the LTTE. It also triggered a massive exodus of Tamils fleeing persecution, establishing large diaspora communities in countries like Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. These communities would later provide crucial financial support to the Tamil separatist movement. Most significantly, Black July transformed what had been primarily a political conflict into a full-scale civil war that would consume the country for the next 26 years.

The Sri Lankan Civil War represents one of the most protracted and devastating conflicts in recent South Asian history. Lasting from 1983 to 2009, this 26-year insurgency pitted the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), led by Velupillai Prabhakaran, against the Sri Lankan government in a struggle that would reshape the nation’s political landscape and claim tens of thousands of lives15. The LTTE fought to establish an independent Tamil state called Tamil Eelam in the northeastern part of the island, motivated by what they perceived as continuous discrimination and violent persecution against Sri Lankan Tamils by the Sinhalese-dominated government5.

What began as a small rebellion in 1983 evolved into a sophisticated insurgency with the LTTE developing capabilities that included conventional military units, a naval wing (Sea Tigers), and even rudimentary air capabilities. At various points during the conflict, the LTTE controlled significant territory in northern and eastern Sri Lanka, establishing parallel governance structures in areas under their control. The group’s use of suicide bombings and targeted assassinations—including the killing of Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991—earned them designation as a terrorist organization by numerous countries.

The war progressed through several distinct phases, with periods of intense fighting interspersed with failed peace attempts. A significant international dimension was added when India intervened in 1987, deploying the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) in an attempt to disarm the Tamil militants and enforce a peace accord. This intervention, which lasted until 1990, ultimately failed in its objectives and resulted in the IPKF becoming embroiled in bitter fighting with the LTTE5. The conflict’s brutality intensified over time, with both sides accused of serious human rights violations including torture, extrajudicial killings, forced disappearances, and the use of child soldiers.

After multiple failed peace processes, including a Norwegian-brokered ceasefire that collapsed in 2006, the Sri Lankan government under President Mahinda Rajapaksa launched a major military offensive in 2008. This final phase of the war was marked by an unprecedented intensity of combat and allegations of severe human rights abuses by both sides. By May 2009, government forces had cornered the remaining LTTE fighters in a small coastal area in the northeast. On May 16, 2009, the Sri Lankan government declared military victory over the LTTE, and on May 17, the LTTE finally admitted defeat5. The conflict concluded officially on May 19 when President Rajapaksa addressed Parliament and confirmed the death of LTTE leader Velupillai Prabhakaran5.

The human cost of this protracted conflict was immense. While precise casualty figures remain disputed, conservative estimates suggest over 100,000 people were killed, with some sources placing the death toll much higher. The war created hundreds of thousands of internally displaced persons and resulted in a significant Tamil diaspora as refugees fled the violence. The final months of the war were particularly controversial, with the United Nations estimating that as many as 40,000 civilians may have died during this period, raising serious questions about potential war crimes by both sides that continue to complicate Sri Lanka’s path to reconciliation.

While the ethnic conflict between Sinhalese and Tamils dominated Sri Lanka’s security landscape, the country also experienced significant political violence from the Marxist-Leninist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front or JVP). The JVP, described as “thoroughly modern revolutionaries” in academic literature, launched two major armed insurrections against the Sri Lankan government that added another dimension to the country’s history of violence6.

The first JVP uprising occurred in 1971, representing an early challenge to the post-independence government. Though ultimately unsuccessful, this insurrection demonstrated the existence of radical leftist sentiment among segments of the population, particularly educated but unemployed Sinhalese youth who felt economically marginalized despite being from the majority ethnic group2. The government’s suppression of this first revolt was swift and brutal, temporarily diminishing the JVP’s operational capabilities.

The second and more significant JVP insurrection took place from 1987 to 1989, concurrent with the ongoing civil war. This uprising, also known as the “1988-1989 revolt” or the “JVP troubles,” was better prepared and more deeply rooted than the 1971 attempt6. The immediate catalyst for this second uprising was the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord of 1987, which brought Indian peacekeepers into Sri Lanka—a development the nationalist JVP vehemently opposed2. The insurrection took the form of a low-intensity conflict characterized by subversion, assassinations, raids, and attacks on both military and civilian targets2.

The military operations of this insurrection were led by the Deshapremi Janatha Viyaparaya (DJV), which functioned as the military wing of the JVP2. The insurgency reached its peak in 1988 and had a significant impact on all Sri Lankan civilians, including those without any political stake in the situation2. The government response was ruthless, employing counter-insurgency operations that often operated outside normal legal constraints. The situation deteriorated further when attacks on civilians by pro-government guerrillas intensified following the election of President Ranasinghe Premadasa2.

A particularly dark period of mass killings began after the ceasefire of the Sri Lankan Civil War and the expulsion of the Indian Peace Keeping Force, resulting in the deaths of many Sri Lankan civilians and multiple Indian expatriates2. The human toll of this insurrection was staggering, with estimates suggesting between 10,000 and 60,000 JVP members and supporters were captured and/or killed, while more than 20,000 people disappeared during this period—presumably victims of extrajudicial executions2.

The dual JVP insurrections illustrate how Sri Lanka’s landscape of violence extended beyond ethnic conflict to encompass class-based and ideological struggles. These leftist uprisings also demonstrate how the Sri Lankan state developed increasingly militarized responses to internal threats, establishing patterns of counter-insurgency that would later be applied in the war against the LTTE. The legacy of the JVP insurrections continues to influence Sri Lankan politics, with the JVP eventually transforming into a legitimate political party that participates in the democratic process today.

The end of the civil war in 2009 did not mark the end of significant violence in Sri Lanka. Despite hopes for a peaceful post-war era, the country has continued to experience episodes of violence, most notably the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings, which represented a new dimension of terrorism with religious rather than ethnic motivations. The post-war period has also been marked by ongoing human rights concerns, political instability, and challenges in addressing the underlying causes of past conflicts.

One of the most devastating attacks in Sri Lanka’s recent history occurred on April 21, 2019. On Easter Sunday, a group of Sri Lankans inspired by the Islamic State carried out six coordinated suicide bombings targeting churches and tourist hotels3. This carefully orchestrated attack killed 269 people, including worshippers attending Easter Sunday services3. The bombings were attributed to National Thowheeth Jama’ath (NTJ), a local Islamist extremist group that had pledged allegiance to the Islamic State.

What made these attacks particularly controversial were subsequent allegations of state complicity or negligence. Four years after the bombings, the Wickremesinghe-led government initiated investigations to probe whether the state intelligence services were complicit in one of the most devastating extremist attacks in Sri Lankan history3. According to a British television report, a man claimed to have arranged a secret meeting between Islamic extremists and a top Sri Lankan intelligence official in 2018, allegedly to create a national security crisis that would benefit the Rajapaksa family politically3. The bombings occurred in April 2019, and within seven months, Gotabaya Rajapaksa was sworn in as president, with his brother Mahinda Rajapaksa becoming prime minister3. These allegations suggest that political manipulation and security failures may have played a role in allowing the attacks to occur, though investigations are ongoing.

The post-war period has also been characterized by persistent human rights concerns, particularly regarding the treatment of former LTTE members, Tamil civilians, and political dissidents. International human rights organizations have documented continued cases of torture, abductions, and extrajudicial actions by security forces, suggesting that patterns of violence established during the war have not been fully addressed. Additionally, land disputes in formerly LTTE-controlled areas, militarization of civilian spaces, and limited accountability for wartime abuses have hindered genuine reconciliation.

Recent years have also seen significant political and economic turmoil in Sri Lanka. The country experienced a devastating economic crisis in 2022, leading to widespread protests, political instability, and the eventual resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. These developments demonstrate the complex interplay between economic factors, governance issues, and the potential for renewed unrest. The continuing investigations into the Easter Sunday bombings highlight ongoing questions about the role of state actors in episodes of violence, as well as the challenges of establishing transparency and accountability in a political system shaped by decades of conflict.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s history reveals a complex tapestry of violence driven by ethnic tensions, political opportunism, and socioeconomic grievances. From the colonial policies that exacerbated ethnic divisions to the devastating civil war that consumed nearly three decades, violence has profoundly shaped the nation’s development and collective psychology. The major episodes of violence—Black July, the Sri Lankan Civil War, the JVP insurrections, and more recent terrorist attacks—demonstrate recurring patterns of radicalization, state overreach, and the exploitation of social cleavages for political gain.

The colonial legacy established dangerous precedents of ethnic favoritism that post-independence governments perpetuated rather than corrected. Discriminatory policies targeting Tamils in the decades following independence created conditions ripe for radicalization and separatist sentiment. Black July represented a critical turning point, transforming simmering tensions into outright warfare that would devastate the country for 26 years. Throughout this period, the parallel JVP insurrections demonstrated how violence in Sri Lanka transcended purely ethnic lines to encompass ideological and class-based dimensions.

Even after the military defeat of the LTTE in 2009, Sri Lanka has struggled to establish a sustainable peace that addresses the root causes of conflict. The Easter Sunday bombings of 2019 introduced a new sectarian dimension to violence in Sri Lanka, while allegations of state complicity raise troubling questions about the persistence of political violence. Recent economic and political crises further illustrate how unresolved tensions and governance failures continue to threaten stability.

Sri Lanka’s experience offers important lessons about the dangers of policies that marginalize minority communities, the devastating long-term consequences of communal violence, and the challenges of post-conflict reconciliation. The path toward lasting peace requires not only security measures but also meaningful efforts to address historical grievances, ensure equal rights and opportunities for all citizens, and establish accountability for past abuses. While significant obstacles remain, understanding the complex history of violence in Sri Lanka is an essential step toward ensuring that future generations can break free from cycles of conflict that have caused so much suffering throughout the nation’s modern history.

Citations:

- https://byjusexamprep.com/current-affairs/sri-lankan-civil-war

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1987%E2%80%931989_JVP_insurrection

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1y8vGPvz-_A

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_July

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sri_Lankan_civil_war

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/B0A26D65FF21D3482B08E9C9E1236415/S0026749X00010908a.pdf/thoroughly_modern_revolutionaries_the_jvp_in_sri_lanka.pdf

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/sri-lankas-president-will-appoint-committee-to-probe-claims-of-complicity-in-2019-easter-sunday-bombings

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-12004081

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1971_JVP_insurrection

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/9/8/ex-sri-lanka-leader-denies-2019-bombings-were-staged-to-help-him-win-polls

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2007/3/27/timeline-of-sri-lankas-civil-war-2

- https://humbernews.ca/2023/04/timeline-sri-lankas-civil-war-resulted-in-the-loss-of-tamil-history/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dPZjgZZsWPU

- https://hir.harvard.edu/sri-lankan-civil-war/

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2009/5/19/timeline-conflict-in-sri-lanka

- https://www.reuters.com/article/world/-sri-lankas-25-year-civil-war-idUSTRE54F166/

- https://www.reuters.com/article/economy/chronology-sri-lankas-two-decade-civil-war-idUSCOL548/

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/27017660

- https://www.jvpsrilanka.com/english/about-us/brief-history/

- https://histecon.fas.harvard.edu/invisible-histories/captions/unruly/index.html

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2644815

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Peoples-Liberation-Front

- https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/sri-lanka/

- https://www.hrcsl.lk/about/history/?lang=en

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Human_rights_abuses_in_Sri_Lanka

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lce074-w_xc

- https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/statements/2024/07/23/statement-prime-minister-mark-41-years-black-july

- https://www.vaticannews.va/en/church/news/2024-04/sri-lanka-anniversary-easter-sunday-bombings-fr-silva-card-zuppi.html

- https://www.aljazeera.com/tag/sri-lanka-bombing/

- https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-statement-easter-sunday-attacks-sri-lanka

- https://www.bbc.com/news/topics/cdmmjkw6krwt

- https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2019/sri-lanka/

- https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/asia-and-the-pacific/south-asia/sri-lanka/report-sri-lanka/

- https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/country-chapters/sri-lanka

- https://1997-2001.state.gov/global/human_rights/1997_hrp_report/srilanka.html

- https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cdp-2024-0066/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_rights_in_Sri_Lanka

- https://refuge.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/refuge/article/download/22007/20676

- https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/remembering-1958-pogrom-2

- https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/7/29/for-sri-lankan-tamils-the-black-july-pogroms-live-on-40-years-later

- https://pearlaction.org/black-july-a-tamil-genocide/

- https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/anatomy-pogrom

- https://www.dw.com/en/remembering-sri-lankas-anti-tamil-pogrom-of-1983/audio-16963089

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1958_anti-Tamil_pogrom

- https://groundviews.org/2023/07/23/anti-tamil-pogrom-of-july-83-root-causes-unaddressed-even-after-40-years/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_military_operations_of_the_Sri_Lankan_civil_war