By Arun Arokianathan

Throughout my journalism career, which began in 1999, I have heard about the horrific protests and violence in the late 1980s—the acrid smell of burning tires, black flags hoisted in defiance, and passionate crowds denouncing what they called “Indian imperialism.” The Indo-Sri Lanka Accord had just been signed, and my parents and senior colleagues often recounted how the streets of Colombo were alive with rage against India’s perceived intervention. These protests soon spiraled into one of Sri Lanka’s darkest periods, with JVP insurgents unleashing a reign of terror that claimed thousands of lives, followed by a brutal government crackdown that saw the disappearance and execution of thousands more—mostly Sinhalese youth from the southern provinces. Villages emptied of young men, roadblocks displayed severed heads as warnings, and an estimated 40,000-60,000 people perished in this fratricidal violence.

Among those leading these fiery protests was a young leftist firebrand named Anura Kumara Dissanayake, whose revolutionary rhetoric against “Indian hegemony” energized demonstrators across the capital. His party, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), was at the center of this bloody insurrection that paralyzed the south of the country through assassinations, general strikes, and targeted killings before it was ruthlessly crushed by government forces.

Last week, I watched from afar as President Dissanayake, once that vocal critic, bestowed Sri Lanka’s highest civilian honour, the ‘Sri Lanka Mitra Vibhushana’ on , upon Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The same hands that once burned effigies of Indian leaders now clasped Modi’s in warm diplomatic embrace. As the ceremonial drums played and dignitaries applauded on my screen, I couldn’t help but wonder: Is this transformation genuine political evolution or merely another performance in Sri Lanka’s long theater of diplomatic expediency?

The Politics of Recognition: Symbol or Substance?

The symbolism was impossible to miss. The conferring of the Sri lanka Mithra Vibhushana on Modi marked only the second time in history that Sri Lanka had bestowed this honor on a foreign leader. The grandiose ceremony, with its elaborate protocols and effusive praise, projected an image of two nations united by mutual respect and shared vision.

Yet in my two decades covering South Asian politics, I’ve learned to look beyond ceremonial gestures. This high-profile recognition comes at a critical juncture for both nations. For Dissanayake’s fledgling government, barely six months in power, the embrace of India represents not just diplomatic outreach but economic necessity. Sri Lanka, still nursing the wounds of its catastrophic 2022 economic collapse, desperately needs India’s continued financial support. The $1.36 billion debt restructuring agreement finalized during Modi’s visit isn’t simply goodwill—it’s oxygen for a nation still gasping for economic breath.

For Modi, this visit reinforces India’s “Neighbourhood First” policy while subtly countering China’s growing influence in the island nation. The seven memorandums of understanding signed—spanning defence, energy, digital infrastructure, and more—form a strategic counterbalance to Beijing’s infrastructure investments across Sri Lanka.

In the diplomatic theater that is South Asian politics, this award ceremony was brilliantly choreographed. But beneath the lights and camera flashes lies the hard reality: this is realpolitik in its purest form, where yesterday’s ideological stances yield to today’s pragmatic necessities.

The Memory of Protest and the Cost of Amnesia

What strikes me most profoundly about this diplomatic pivot is not that it happened—politics, after all, is the art of the possible—but the collective amnesia that seems to accompany it.

Through my readings and conversations with senior journalists who witnessed those turbulent times, I’ve developed a clear picture of a much younger Dissanayake, then a prominent figure in the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), who built his political capital on fierce resistance to what he termed “Indian interference” in Sri Lankan affairs. His party consistently opposed the implementation of the 13th Amendment—a direct outcome of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord that sought to devolve power to provincial councils as a solution to the ethnic conflict.

What’s often glossed over in diplomatic retellings is the horrific violence that engulfed Sri Lanka during this period. The JVP insurgency claimed thousands of lives through assassinations, bombings, and targeted killings. The government’s response was equally brutal, with counter-insurgency operations resulting in disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and mass graves. By some estimates, between 40,000-60,000 people lost their lives during this period, the vast majority being Sinhalese youth from southern provinces like Hambantota, Matara, and Galle. This bloodshed forms an uncomfortable backdrop to today’s diplomatic pleasantries—particularly since Dissanayake’s political origins lie within the movement that was at the center of this violent chapter.

Now, as President, Dissanayake spoke warmly of India as Sri Lanka’s “closest neighbor and friend.” Not once during the high-profile visit was there mention of his previous stance on India or the 13th Amendment. This pivot is either remarkable political maturation or calculated amnesia—and I suspect more of the latter than the former.

The willingness to shed inconvenient ideological positions is not unique to Sri Lanka’s politics, but it does raise profound questions about the authenticity of today’s diplomatic overtures. If fundamental views on sovereignty, autonomy, and ethnic reconciliation can be so easily shelved for expedient diplomacy, what guarantees the durability of today’s commitments?

The Lingering Tamil Question: The Elephant in Every Room

Throughout the three-day visit filled with grand announcements about solar power projects, railway upgrades, and defense cooperation, one issue remained conspicuously absent from the foreground: the unresolved Tamil question that has defined—and sometimes devastated—Sri Lankan politics for generations.

The symbolic omission was telling. Despite Modi’s visit spanning multiple venues and occasions, the absence of Tamil on welcome banners and official communications spoke volumes. In a nation where Tamil holds official language status—at least constitutionally since 1987—such omissions aren’t accidental but indicative of deeper institutional neglect.

More substantively, the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord of 1987—the very agreement that sparked such vehement opposition from Dissanayake’s political antecedents—remains largely unimplemented in its core principles. Its provisions for Tamil as an official language, meaningful devolution of power to provinces, and equal political participation for minority communities have been diluted, delayed, or outright ignored through successive governments.

Although the armed conflict came to a brutal end in 2009 with the military defeat of the LTTE, there has been no honorable peace achieved through meaningful reconciliation or political devolution. This failure continues to prevent the full participation of Sri Lankan Tamils in governance. The current cabinet, like most before it, features minimal Tamil representation in key decision-making positions. This systemic exclusion from power directly contradicts the spirit of the 13th Amendment and perpetuates the marginalization that fueled decades of conflict.

Since I began reporting on the region in 1999, I’ve witnessed five different Sri Lankan administrations promise meaningful reconciliation and constitutional reform. Each has used sophisticated diplomatic language and international goodwill to buy time while maintaining the status quo of centralized Sinhala-Buddhist dominance. The Dissanayake government, despite its progressive credentials, shows troubling signs of continuing this pattern.

Modi’s visit offered a perfect opportunity to signal genuine commitment to the full implementation of the 13th Amendment—a long-standing Indian position—yet the joint statements remained vague on this critical issue, focusing instead on infrastructure projects and economic cooperation.

The Singapore Contrast: A Path Not Taken

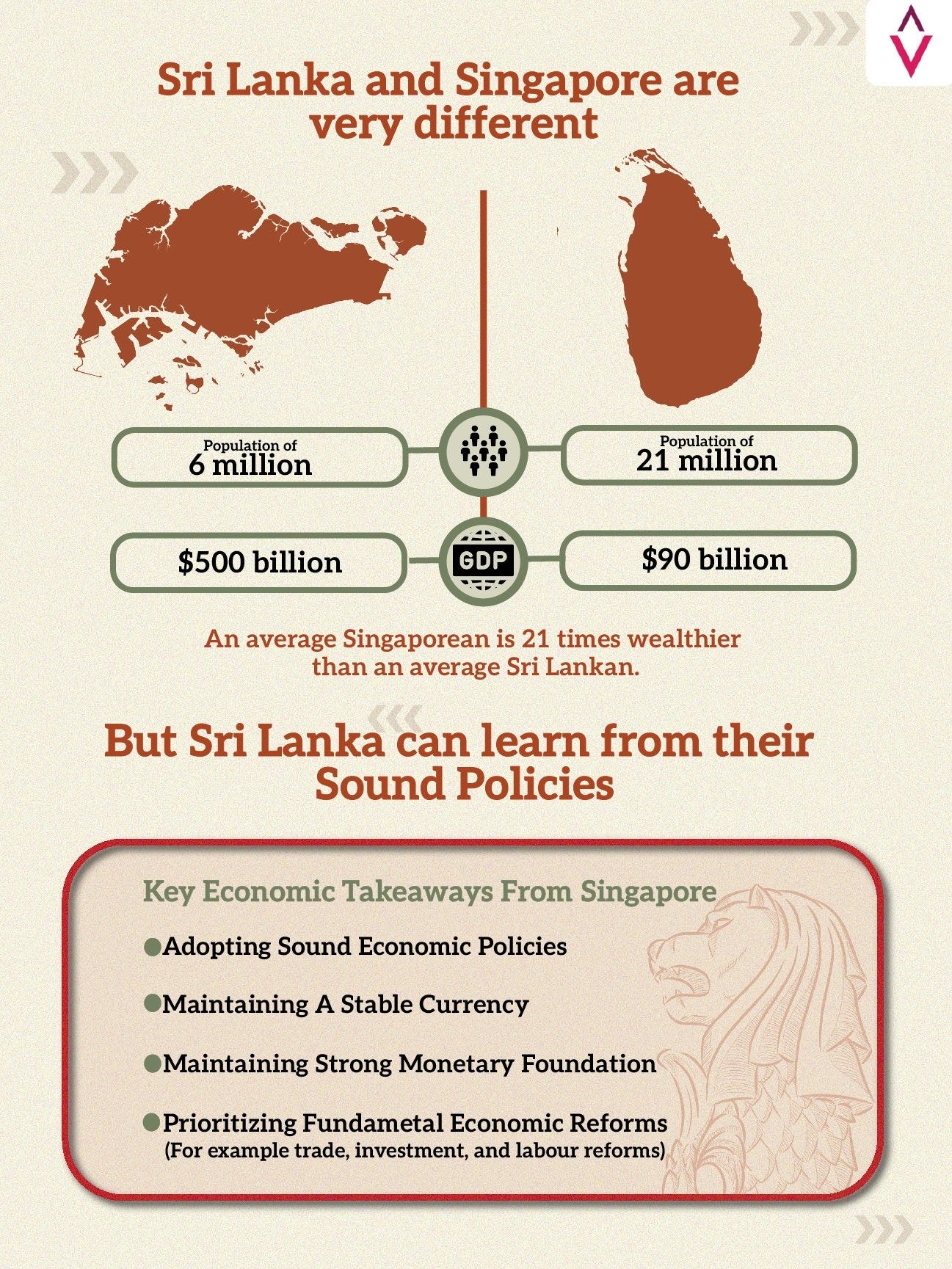

As I reflected on Sri Lanka’s tortuous journey through ethnic conflict and reconciliation, my mind drifted to another island nation I’ve frequently covered: Singapore. The contrast couldn’t be more striking.

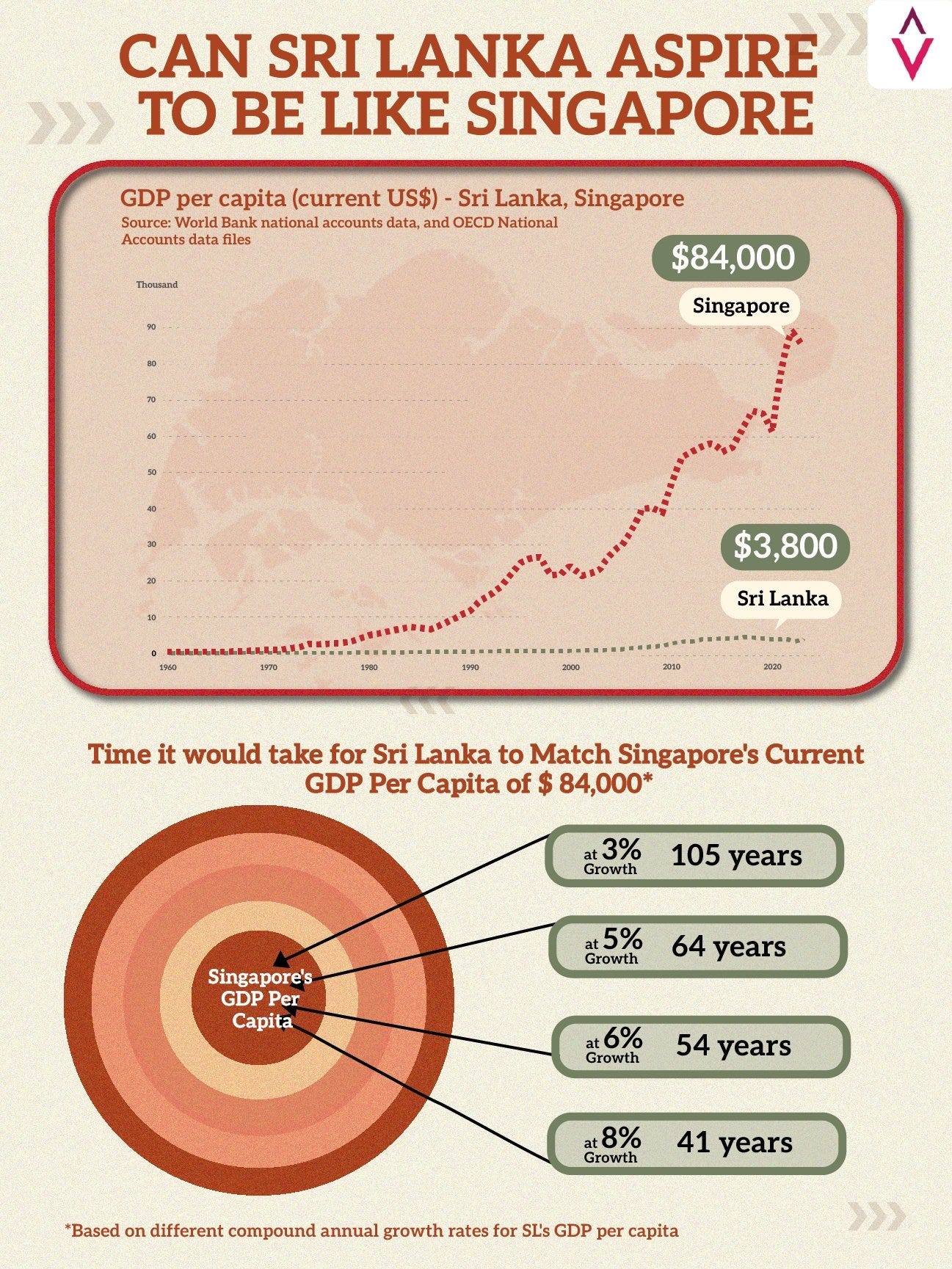

In 1960, Singapore’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew looked to Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was then known) as a model of post-colonial success. He admired its strong infrastructure, educated population, and promising trajectory. Today, the economic divergence is staggering: Singapore’s GDP per capita stands at $84,000 compared to Sri Lanka’s $3,800.

But what’s often overlooked in this comparison is not just economic policy but Singapore’s foundational commitment to linguistic and ethnic inclusion. From its inception, Singapore enshrined four official languages: English, Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil. This wasn’t just symbolic recognition—it was structural inclusion backed by institutional support.

The results speak for themselves. Today, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, of Tamil origin, serves as Singapore’s President. The Cabinet consistently includes members from all communities. The city-state’s public communications, from road signs to government websites, reflect its multilingual reality.

Sri Lanka, with its parallel ethno-linguistic diversity, chose a different path. Despite constitutional recognition of Tamil as an official language, the implementation has been halfhearted at best. The contrast appears even in seemingly minor details.

This isn’t merely about symbolic representation. Singapore’s inclusive approach has contributed significantly to its social stability and economic miracle. By ensuring that no community feels alienated from the national project, it minimized the internal tensions that have repeatedly derailed Sri Lanka’s development.

Even with an ambitious, dream-level 8% annual growth, it would take Sri Lanka another four decades to reach Singapore’s level of economic prosperity. But without genuine national harmony—built on meaningful power devolution, sincere reconciliation, and credible accountability—this vision will remain a distant daydream.

True harmony would open the door to harnessing the full potential of the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora, whose economic strength, global networks, and wealth of expertise could become a powerful engine for national development.

The Burden of Superficial Change

The pattern is depressingly familiar. For decades, successive Sri Lankan governments have mastered the art of diplomatic gestures while resisting meaningful reforms that would address the root causes of ethnic tension. International goodwill is earned through elaborate ceremonies and promising joint statements, only for implementation to fade once the spotlight moves elsewhere.

I fear we may be witnessing another cycle of this performance. The conferring of Sri Lanka’s highest honor on Modi, the signing of multiple MoUs, and the grand statements about bilateral friendship are impressive theater. But without concrete action on fundamental issues of constitutional reform and genuine power-sharing, they risk becoming another footnote in Sri Lanka’s long history of diplomatic distractions.

India, having invested heavily in Sri Lanka’s stability and development, must look beyond ceremonial honors and economic agreements. Its strategic interest lies not just in countering Chinese influence but in ensuring sustainable peace in its immediate neighborhood. This requires holding the Sri Lankan leadership accountable for meaningful implementation of previously agreed principles, particularly those enshrined in the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord.

Beyond Gestures: The Path Forward

As I followed the conclusion of the state visit, I found myself reflecting on the distance between diplomatic spectacle and ground reality. More than two decades of covering South Asian politics has taught me that unresolved questions of identity, language, and dignity don’t disappear with time—they merely simmer beneath the surface, occasionally erupting with devastating consequences.

The path forward for Sri Lanka—and for productive Indo-Sri Lankan relations—requires moving beyond symbolic gestures to structural change. President Dissanayake, with his progressive credentials and fresh mandate, has a rare opportunity to break from the pattern of his predecessors. But this would require more than hosting successful state visits and receiving accolades for economic initiatives.

It would mean confronting the uncomfortable truths about Sri Lanka’s unresolved ethnic question, implementing the long-delayed promises of the 13th Amendment, and ensuring that Tamil citizens feel fully included in the national project—not just through constitutional provisions but through lived experience.

For Prime Minister Modi and India, it means leveraging their considerable influence not just for strategic positioning vis-à-vis China but for lasting reconciliation that serves both moral and practical interests. The stability of the region depends not on how many honors are exchanged but on how fundamentally the underlying tensions are addressed.

Sri Lanka stands once again at a crossroads of possibility. The question remains whether this latest diplomatic performance signals genuine transformation or merely another act in the long-running theater of postponed promises. For the sake of all communities who call this island home, I hope it’s the former—but my years of witnessing Sri Lankan politics leave me guardedly skeptical.

History teaches us that problems avoided rarely solve themselves. They merely await their moment to return—often with redoubled force.

Arun Arokianathan is an Asia Journalism Fellow and a Chevening South Asia Journalism Programme (SAJP) Fellow. Follow his work and insights on Twitter @aroarun and connect with him on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/in/arunarokianathan/